Blog posts

Using DBus from Javascript in Cockpit

Note: This post has been updated for changes in Cockpit 0.90 and later.

Cockpit is a user interface for servers. As we covered in the last tutorial you can add user interface component to Cockpit, and build your own parts of the Server UI.

Much of Cockpit interacts with the server using DBus. We have a powerful yet simple API for doing that, and you should use DBus too when building your own Cockpit user interfaces. For this tutorial you’ll need at least Cockpit 0.41. A few tweaks landed in that release to solve a couple rough edges we had in our DBus support. You can install it in Fedora 21 or build it from git.

Here we’ll make a package called zoner which lets you set the time zone of your server. We use the systemd timedated DBus API to do actually switch time zones.

I’ve prepared the zoner package here. It’s just two files. To download them and extract to your current directory, and installs it as a Cockpit package:

$ wget http://cockpit-project.org/files/zoner.tgz -O - | tar -xzf -

$ cd zoner/

$ mkdir -p ~/.local/share/cockpit

$ ln -snf $PWD ~/.local/share/cockpit/zoner

Previously we talked about how packages are installed, and what manifest.json does so I won’t repeat myself here. But to make sure the above worked correctly, you can run the following command. You should see zoner listed in the output:

$ cockpit-bridge --packages

...

zoner: .../.local/share/cockpit/zoner

...

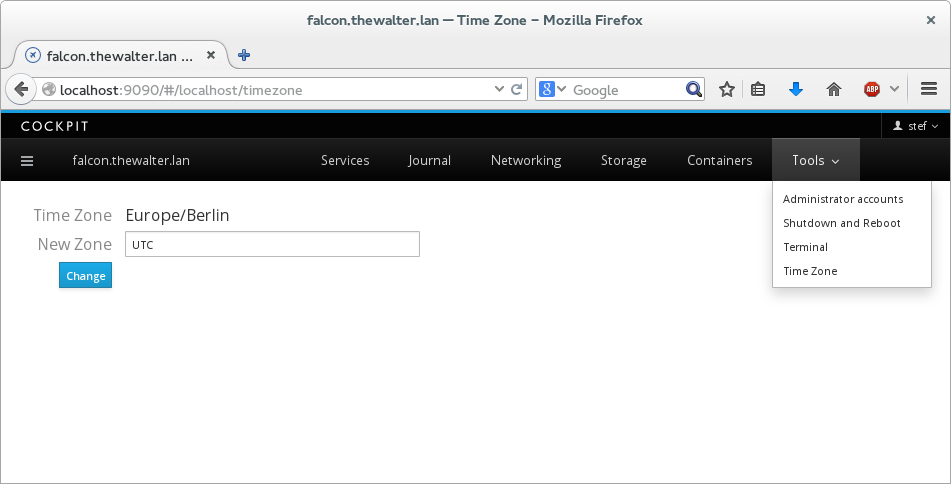

If you’re logged into Cockpit on this machine, first log out. And log in again. Make sure to log into Cockpit with your current user name, since you installed the package in your home directory. You should now see a new item in the Tools menu called Time Zone:

Try it out by typing Australia/Tasmania in the box, and clicking Change. You should see that the Time Zone changes. You can verify this by typing the following on the same server in a terminal:

$ date

Sa 15. Nov 01:48:01 AEDT 2014

Try typing an invalid timezone like blah, and you’ll see an error message displayed. Now try changing the timezone from the terminal using the timedatectl command while you have Cockpit open displaying your Time Zone screen:

$ sudo timedatectl set-timezone UTC

You should see your timezone on your screen update immediately to reflect the new state of the server. So how does this work? Lets take a look at the zoner HTML:

<head>

<title>Time Zone</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<link href="../base1/cockpit.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet">

<script src="../base1/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="../base1/cockpit.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container-fluid" style='max-width: 400px'>

<table class="cockpit-form-table">

<tr>

<td>Time Zone</td>

<td><span id="current"></span></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>New Zone</td>

<td><input class="form-control" id="new" value="UTC"></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><button class="btn btn-default btn-primary" id="change">Change</button></td>

<td><span id="failure"></span></td>

</tr>

</table>

</div>

<script>

var input = $("#new");

var current = $("#current");

var failure = $("#failure");

$("#change").on("click", change_zone);

var service = cockpit.dbus('org.freedesktop.timedate1');

var timedate = service.proxy();

$(timedate).on("changed", display_zone);

function display_zone() {

current.text(timedate.Timezone);

}

function change_zone() {

var call = timedate.SetTimezone(input.val(), true);

call.fail(change_fail);

failure.empty();

}

function change_fail(err) {

failure.text(err.message);

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

First we include jquery.js and cockpit.js. cockpit.js defines the basic API for interacting with the system, as well as Cockpit itself. You can find detailed documentation here.

<script src="../base1/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="../base1/cockpit.js"></script>

We also include the cockpit.css file to make sure the look of our tool matches that of Cockpit. The HTML is pretty basic, defining a little form where the current timezone is shown, a field to type an address, a button to click change to a new one, and an area to show errors.

In the javascript code, first we get a bunch of variables pointing to the HTML elements we want to interact with.

Next we attach a handler to the Change button so that the change_zone() function is called when it is clicked.

$("#change").on("click", change_zone);

Next we connect to the timedated DBus service using the cockpit.dbus() function:

var service = cockpit.dbus('org.freedesktop.timedate1');

Now we make a proxy which represents a particular DBus interface containing methods and properties. Simple services have only one interface. When more than one interface or instance of that interface is present, there are additional arguments to the .proxy() method that you can specify.

var timedate = service.proxy();

Each interface proxy has a "changed" event we can connect to. When properties on the proxy change, or are received for the first time, this event is fired. We use this to call our display_zone() function and update the display of the current time zone:

$(timedate).on("changed", display_zone);

`Timezone` is a property on the [timedated DBus interface](http://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/timedated/). We can access these properties directly, and the proxy will keep them up to date. Here we use the property to update our display of the current time zone:

function display_zone() {

current.text(timedate.Timezone);

}

`SetTimezone` is a method on the [timedated DBus interface](http://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/timedated/) interface, and we can invoke it directly as we would a javascript function. In this case we pass the arguments the DBus method expects, a `timezone` string, and a `user_interaction` boolean.

function change_zone() {

var call = timedate.SetTimezone(input.val(), true);

In a web browser you cannot block and wait until a method call completes. Anything that doesn’t happen instantaneously gets its results reported back to you by means of callback handlers. jQuery has a standard interface called a promise. You add handlers by calling the .done() or .fail() methods and registering callbacks.

call.fail(change_fail);

failure.empty();

}

The change_fail() displays any failures that happen. In this case, SetTimezone DBus method has no return value, however if there were, we could use something like call.done(myhandler) to register a handler to receive them.

Notice that we relied on DBus to tell us when things changed and just updated the display from our event handler. That way we reacted both when the time zone changed due to an action in Cockpit, as well as an action on the server.

Again this is a simple example, but I hope it will whet your appetite to what Cockpit can do with DBus. Obviously you can also do signal handling, working with return values from methods, tracking all instances of a given interface, and other stuff you would expect to do as a DBus client.

Creating Plugins for the Cockpit User Interface

Note: This post has been updated for changes in Cockpit 0.90 and later.

Cockpit is a user interface for servers. And you can add stuff to that user interface. Cockpit is internally built of various components. Each component is HTML, with Javascript logic that makes it work, and CSS to make it pretty.

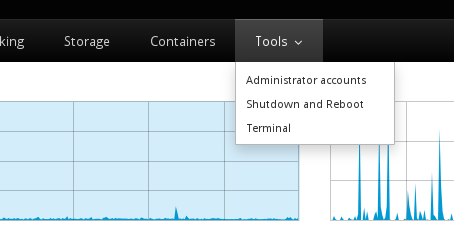

It’s real easy to create these components. Tools are components that show up in the Tools menu in Cockpit:

For example the Terminal that you see there is implemented as a tool. But lets make ourselves another one. For this tutorial you’ll need Cockpit 0.41. You can install it in Fedora 21 or build it from git.

So break out your terminal, lets make a package called pinger that checks whether your server has network connectivity to the Internet by pinging another host. Nothing too fancy. We’ll just be spawning a process on the server to do the work. I’ve prepared it for you as an example here, and we can look it over, and modify it. To download the example to your current directory:

$ wget http://cockpit-project.org/files/pinger.tgz -O - | tar -xzf -

$ cd pinger/

Components, and more specifically their HTML and Javascript files, live in package directories. In the package directory there’s also a manifest.json file which tells Cockpit about the package. The pinger directory above is such a package. It’s manifest.json file looks like this:

{

"version": 0,

"tools": {

"pinger": {

"label": "Pinger",

"path": "ping.html"

}

},

"content-security-policy": "default-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval'"

}

The manifest above has a "tools" subsection. Each tool is listed in the Tools menu by Cockpit. The "path" is the name of the HTML file that implements the tool, and the "label" is the text to show in the Tools menu.

You’ll notice that we haven’t told Cockpit about the package yet. To do so you either place or symlink the package into one of two places:

~/.local/share/cockpit

In your home directory, for user specific packages, and ones that you’re working on. You can edit these on the fly and just refresh your browser to see changes./usr/share/cockpit

For installed packages available to all users. These should not be changed while Cockpit is running.

Since we’re going to be messing around with this package, lets symlink it into the former location.

$ mkdir -p ~/.local/share/cockpit

$ ln -snf $PWD ~/.local/share/cockpit/pinger

You can list which Cockpit packages are installed using the following command, and you should see pinger listed among them:

$ cockpit-bridge --packages

...

pinger: /home/.../.local/share/cockpit/pinger

...

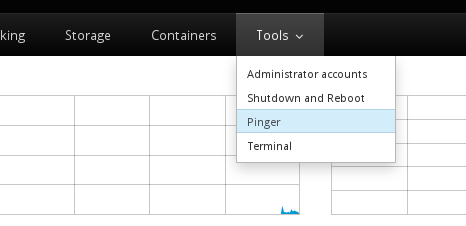

If you’re logged into Cockpit on this machine, first log out. And log in again. Make sure to log into Cockpit with your current user name, since you installed the package in your home directory. You should now see a new item in the Tools menu:

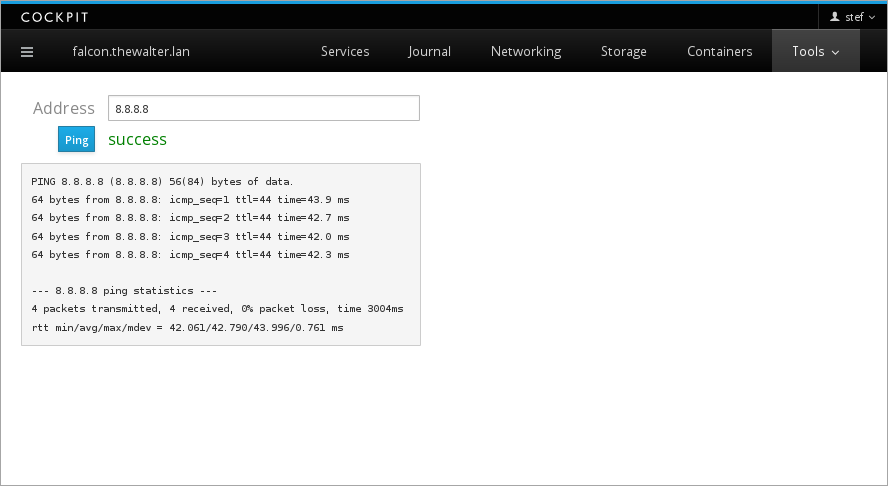

The pinger tool itself looks like this:

Lets take a look at the pinger HTML, and see how it works.

<head>

<title>Pinger</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<link href="../base1/cockpit.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet">

<script src="../base1/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="../base1/cockpit.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container-fluid" style='max-width: 400px'>

<table class="cockpit-form-table">

<tr>

<td>Address</td>

<td><input class="form-control" id="address" value="8.8.8.8"></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><button class="btn btn-primary" id="ping">Ping</button></td>

<td><span id="result"></span></td>

</tr>

</table>

<p><pre id="output"></pre></p>

</div>

<script>

var address = $("#address");

var output = $("#output");

var result = $("#result");

$("#ping").on("click", ping_run);

function ping_run() {

var proc = cockpit.spawn(["ping", "-c", "4", address.val()]);

proc.done(ping_success);

proc.stream(ping_output);

proc.fail(ping_fail);

result.empty();

output.empty();

}

function ping_success() {

result.css("color", "green");

result.text("success");

}

function ping_fail() {

result.css("color", "red");

result.text("fail");

}

function ping_output(data) {

output.append(document.createTextNode(data));

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

First we include jquery.js and cockpit.js. cockpit.js defines the basic API for interacting with the system, as well as Cockpit itself. You can find detailed documentation here.

<script src="../base1/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="../base1/cockpit.js"></script>

We also include the cockpit.css file to make sure the look of our tool matches that of Cockpit. The HTML is pretty basic, defining a little form with a field to type an address, a button to click to start the pinging, and an area to present output and results.

In the javascript code, first we get a bunch of variables pointing to the HTML elements we want to interact with.

Next we attach a handler to the Ping button so that the ping_run() function is called when it is clicked.

$("#ping").on("click", ping_run);

function ping_run() {

In the ping_run() function is where the magic happens. cockpit.spawn is a function, documented here that lets you spawn processes on the server and interact with them via stdin and stdout. Here we spawn the ping command with some arguments:

var proc = cockpit.spawn(["ping", "-c", "4", address.val()]);

In a web browser you cannot block and wait until a method call completes. Anything that doesn’t happen instantaneously gets its results reported back to you by means of callback handlers. jQuery has a standard interface called a promise. You add handlers by calling the .done() or .fail() methods and registering callbacks. proc.stream() registers a callback to be invoked whenever the process produces output.

proc.done(ping_success);

proc.stream(ping_output);

proc.fail(ping_fail);

...

}

The ping_success() and ping_fail() and ping_output() update the display as you would expect.

So there you go … it’s a simple plugin to start off with … next time we’ll cover how to use DBus, and then the real fun begins.

DBus is powerful IPC

D-Bus is powerful IPC Cockpit is heavily built around DBus. We send DBus over our WebSocket transport, and marshal them in JSON.

DBus is powerful, with lots of capabilities. Not all projects use all of these, but so many of these capabilities are what allow Cockpit to implement its UI.

- Method Call Transactions

- Object Oriented

- Efficient Signalling

- Properties and notifications

- Race free watching of entire Object trees for changes

- Broadcasting

- Discovery

- Introspection

- Policy

- Activation

- Synchronization

- Type-safe Marshalling

- Caller Credentials

- Security

- Debug Monitoring

- File Descriptor Passing

- Language agnostic

- Network transparency

- No trust required

- High-level error concept

- Adhoc type definitions

Lennart goes into these further in a kdbus talk, as well as some of the weaknesses of DBus.

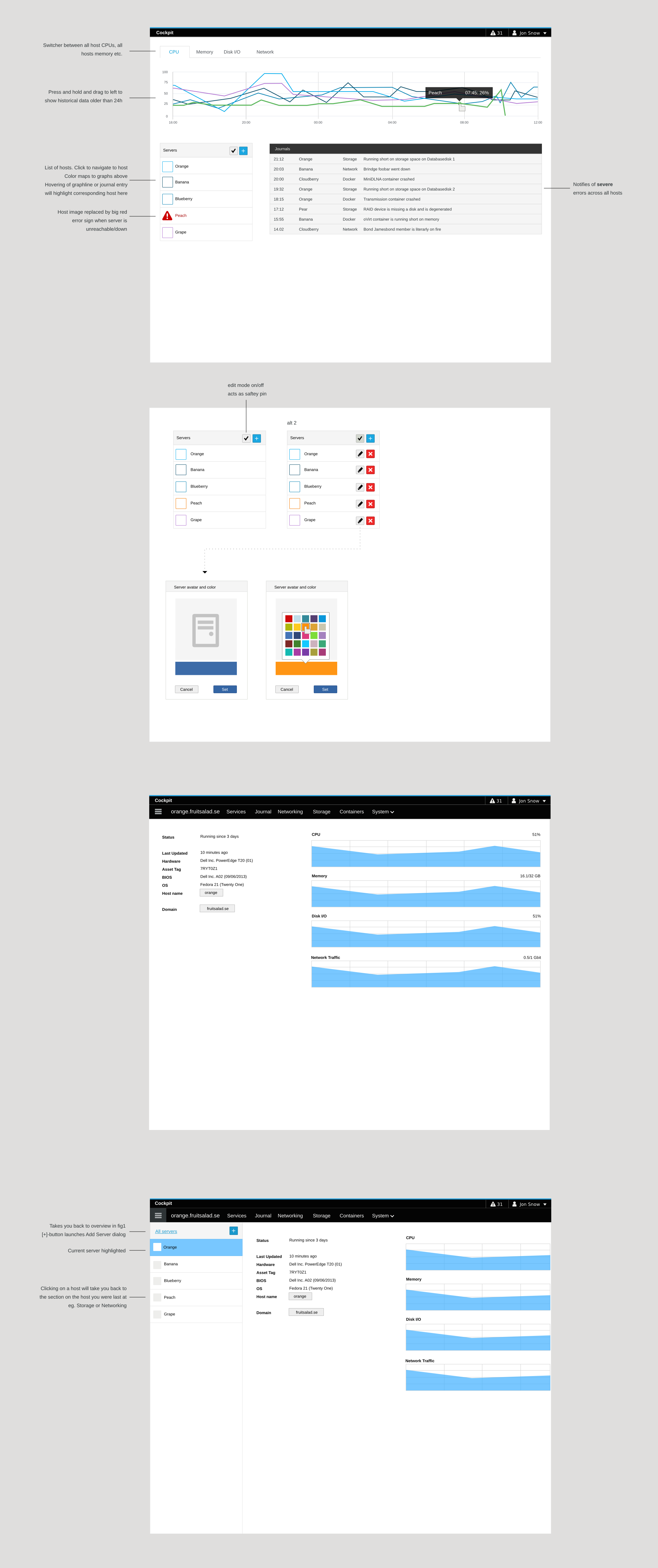

Cockpit Multi-Server Dashboard

Andreas and Marius have been working on implementing a new multi-server dash board for Cockpit. It’s really looking great.

The goal here is that the dash board should work with either one server or several, and give you an overview of what’s going on. Problems that require attention should be highlighted clearly. You should be able to click in spots to jump either to a server, a sub-system, a service/container/pod or to the source of a problem.

The graphs will be correlated across multiple machines, and draggable. Hopefully down road we’ll be using a source of data like PCP to gather the data more consistently. Problems will show up on the graphs as clickable. You can add and remove servers, and we want to show the state of important services/server applications/pods on those servers.

Once the basic code has landed, it would be good to tie this into Kubernetes as well. If running a Kubernetes cluster, and Cockpit is loaded on the master, we should use information from Kubernetes to populate the dashboard.

Here are some wireframes, click to expand:

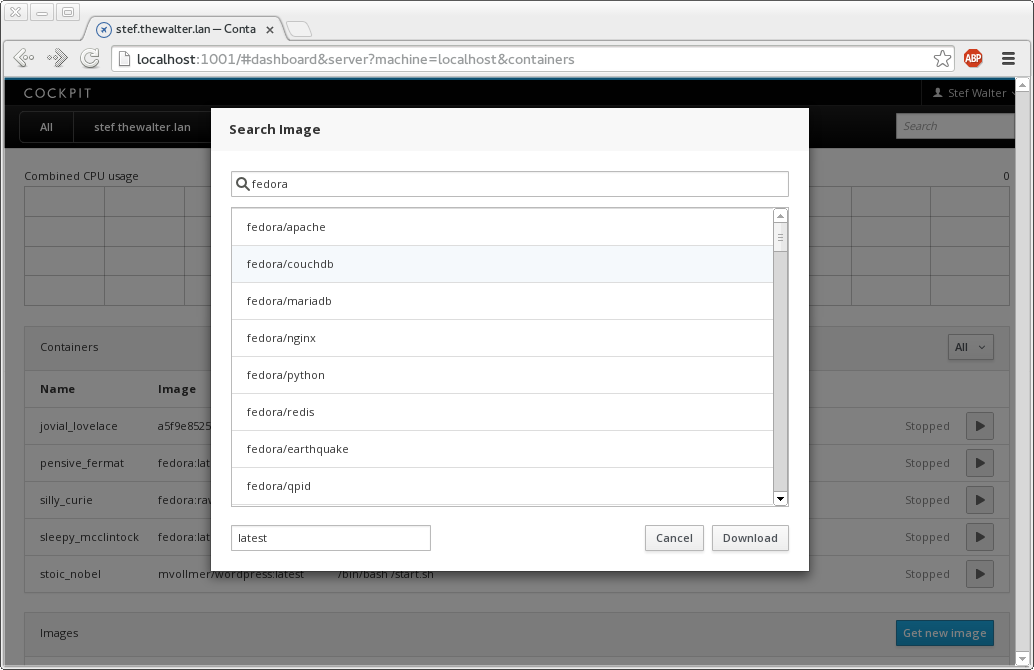

Cockpit has Docker pull support

Cockpit 0.12 now has support for pulling Docker images from the Docker registry.

Unfortunately Docker doesn’t have support for cancelling the pull of an image. So that sort of hampers the UI a bit. At least for now.

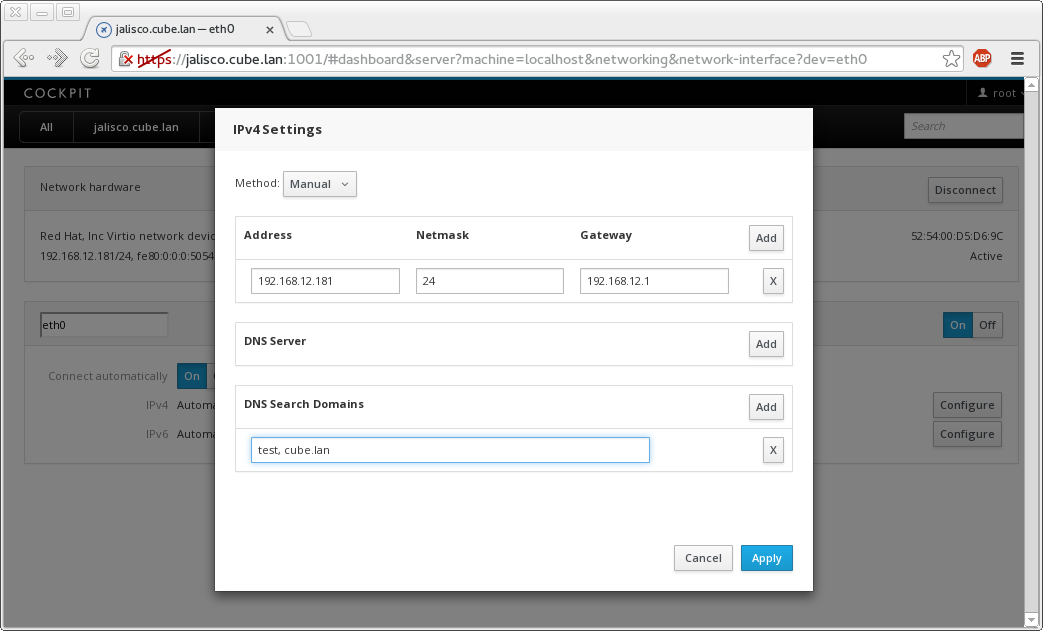

Cockpit Simple Networking Configuration

Cockpit 0.11 now has an all new simple Networking UI. Still some work to do, but it’s coming together. You can see it here:

Cockpit does Docker

Here’s a short video showing how Cockpit manages Docker containers. Cockpit is in RHEL branding here, but it’s basically the same thing as you get from cockpit-project.org

This UI is going to be refined somewhat, but it’s nice to see things coming together.

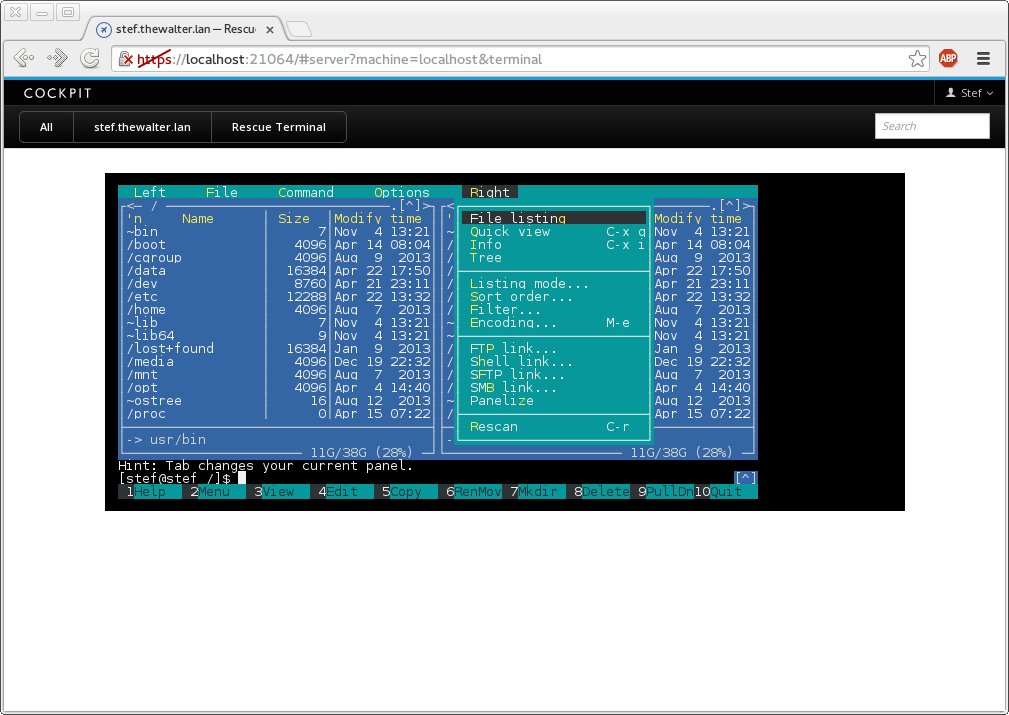

Cockpit has a terminal

Cockpit 0.5 now has a nice terminal in a web browser. AKA term.js is awesome.

Introducing Cockpit

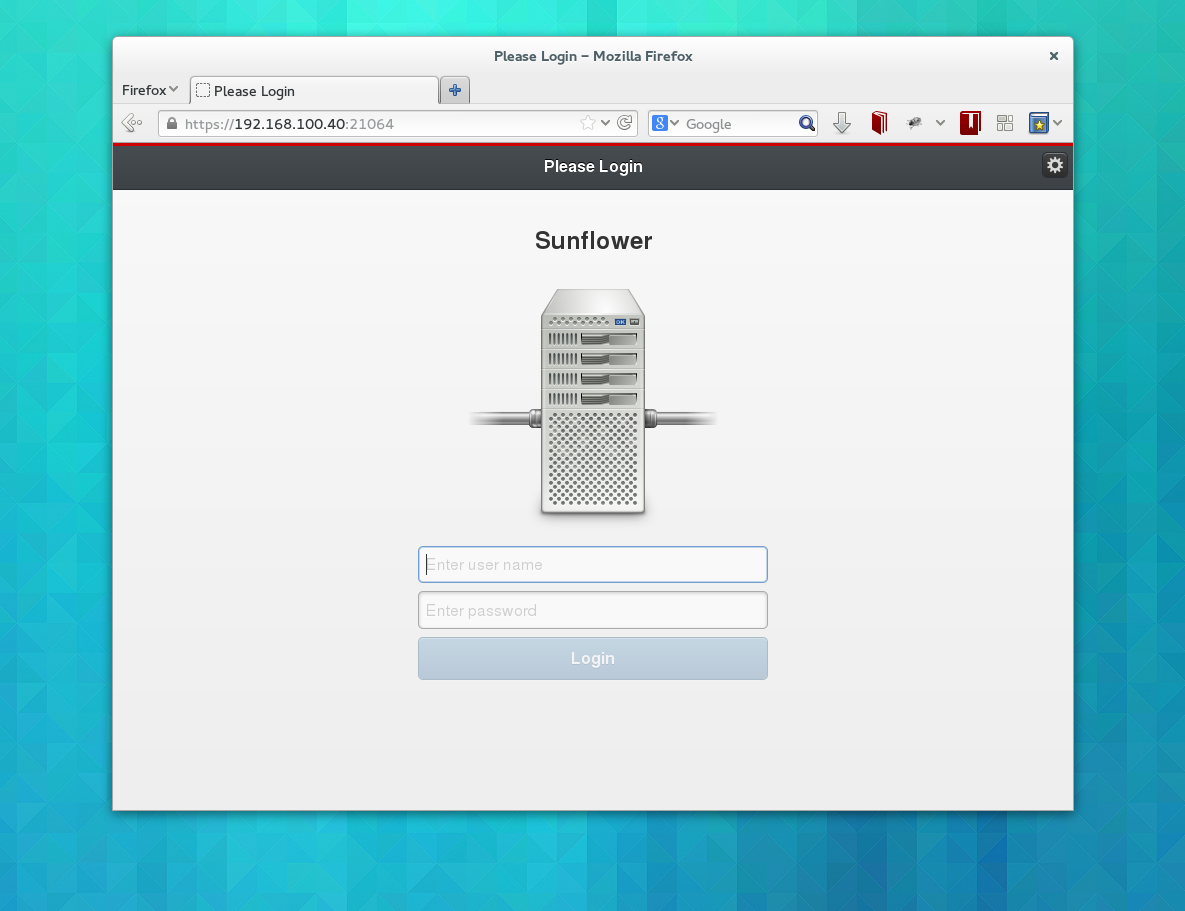

Gave a talk at DevConf in Brno about the project a bunch of us have been working on: Cockpit. It’s a UI for Linux Servers. Currently in the prototype stage…

Hopefully there’ll be a video of the talk available soon. You can try out the Cockpit prototype in Fedora like so:

# yum install --enablerepo=updates-testing cockpit

# setenforce 0 # issue 200

# systemctl enable cockpit-ws.socket

$ xdg-open http://localhost:21064

**Don't run this on a system you care about (yet).** Sorry about the

certificate warning. Groan … I know … working on that.

Needless to say I’m excited about where this is going…